Szemerédi's Regularity Lemma

One of the guiding principles in extremal combinatorics is that large, complicated objects often admit useful approximate descriptions. For graphs, a natural approach is to partition the vertex set into a moderate number of pieces and ask whether the edge distribution between these pieces has some uniformity.

The Regularity Lemma asserts that this can always be done: every large graph can be approximated, at a coarse scale, by a partition in which almost all pairs of vertex classes behave in a pseudorandom fashion. That is, the edge density between two classes is essentially stable, in the sense that it does not fluctuate significantly when one restricts to large subsets. This allows one to replace the original graph with a bounded “reduced graph,” where the vertices correspond to classes and the edges correspond to regular pairs of sufficient density.

From this point of view, many difficult problems about embedding or counting subgraphs are reduced to finite, manageable questions on the reduced graph. Once the graph is approximated by a partition in which most pairs look uniform, one can analyze its global behaviour using only this coarse description. Uniformity ensures that the edge counts between large subsets align closely with what the densities predict, so patterns identified in the reduced graph can be faithfully realized in the original graph. This strategy—simplify, analyze at a reduced scale, and then lift back—has become one of the central tools of modern combinatorics, allowing local randomness to be systematically converted into global structure.

Basic Definitions

Now, how should we define what it means for the edges between two vertex sets to look random? We begin by defining what edge density means. A natural way to define randomness between two vertex sets is to ask whether their edges are distributed approximately uniformly. To capture this, we require that no large subset of either side reveals a very different density of edges than the whole pair.

Edge Density

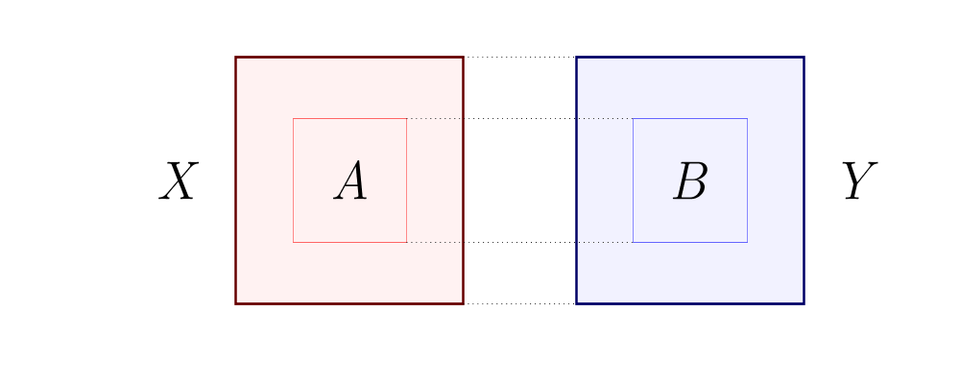

Let \(G=(V,E)\) be a graph and let \(A,B \subseteq V\) be disjoint nonempty sets. The edge density between \(A\) and \(B\) is defined as

$$d(A,B) := \frac{e(A,B)}{\vert A\vert \,\vert B\vert },$$

where \(e(A,B)\) is the number of edges with one endpoint in \(A\) and one in \(B\).

\(\varepsilon\)-Regular Pair

Given \(\varepsilon > 0\), a pair \((A,B)\) of disjoint vertex sets is said to be \(\varepsilon\)-regular if for all subsets \(X \subseteq A\) and \(Y \subseteq B\) with \(\vert X\vert \geq \varepsilon \vert A\vert\) and \(\vert Y\vert \geq \varepsilon \vert B\vert\), one has

$$\bigl\vert \, d(X,Y) - d(A,B) \,\bigr\vert \leq \varepsilon.$$

In other words, the density between \(A\) and \(B\) is essentially uniform across all large enough sub-pairs.

We now define what it means for a partition to be random-like.

\(\varepsilon\)-Regular Partition

A partition of \(V\) into \(k\) classes

$$\mathcal{P} = \{ V_1, V_2, \ldots, V_k \}$$

is called an \(\varepsilon\)-regular partition if

$$\sum_{\substack{(V_i,V_j) \ \text{not } \varepsilon\text{-regular}}} |V_i|\,|V_j| \;\;\leq\;\; \varepsilon \, |V|^2.$$

We have previously mentioned how every graph has a partition in which almost all pairs of vertex classes behave in a pseudorandom fashion. Having introduced the notion of an \(\varepsilon\)-regular partition, one might naturally ask how large the partition must be, as a function of the graph size and \(\varepsilon\). One of the most striking and beautiful features of combinatorics is that the answer depends only on \(\varepsilon\), and is in fact independent of the size of the graph. This Ramsey-like phenomenon is the content of Szemerédi’s Regularity Lemma.

Szemerédi's Regularity Lemma

For every \(\varepsilon > 0\), there exists an integer \(M = M(\varepsilon)\) such that every finite graph \(G\) has an \(\varepsilon\)-regular partition of the vertex set of \(G\) into at most \(M\) parts.

Proof

At first sight, the Regularity Lemma looks like a forbiddingly difficult statement to prove: one has to somehow enforce uniform edge distributions across almost all pairs in a partition of arbitrary size. The key insight is the so-called energy increment argument. One defines a simple quantitative measure of how well a partition captures the structure of a graph—often called the energy of the partition—by averaging squared edge densities across the pairs. If a partition is not yet \(\varepsilon\)-regular, then one can refine it in such a way that this energy strictly increases by a definite amount. Since the energy is bounded above, this process cannot continue indefinitely, and so after finitely many steps one arrives at an \(\varepsilon\)-regular partition. The elegance of this method lies in turning what seems an intractable global requirement into the repeated local act of improving a potential function.

Definition (Energy of a pair). Let \(U, W \subseteq V\) with \(\vert V\vert = n\). The energy of the pair \((U,W)\) is defined by

\[q(U,W) := \frac{\vert U\vert \,\vert W\vert }{n^{2}} \, d(U,W)^{2}.\]For partitions \(\mathcal{P}_U = \{ U_1, \ldots, U_k \}\) of \(U\) and \(\mathcal{P}_W = \{ W_1, \ldots, W_\ell \}\) of \(W\), we define the energy to be the sum of the energies between each pair of parts:

\[q(\mathcal{P}_U, \mathcal{P}_W) := \sum_{i=1}^{k} \sum_{j=1}^{\ell} q(U_i, W_j).\]Finally, for a partition \(\mathcal{P} = \{ V_1, \ldots, V_k \}\) of \(V\), define the energy of \(\mathcal{P}\) to be \(q(\mathcal{P}) := q(\mathcal{P}, \mathcal{P}).\)

Specifically,

\[q(\mathcal{P}) = \sum_{i=1}^{k} \sum_{j=1}^{k} q(V_i, V_j) = \sum_{i=1}^{k} \sum_{j=1}^{k} \frac{\vert V_i\vert \,\vert V_j\vert }{n^{2}} \, d(V_i, V_j)^{2}.\]Note that energy is always between \(0\) and \(1\), since edge density is at most $1$:

\[q(\mathcal{P}) = \sum_{i=1}^{k} \sum_{j=1}^{k} \frac{\vert V_i\vert \,\vert V_j\vert }{n^{2}} \, d(V_i, V_j)^{2} \;\;\leq\;\; \sum_{i=1}^{k} \sum_{j=1}^{k} \frac{\vert V_i\vert \,\vert V_j\vert }{n^{2}} = 1.\]To be continued…