Ramsey Theory

Early steps in Additive Combinatorics

A central idea in Ramsey theory is that complete disorder cannot persist. In any sufficiently large structure, some degree of order is guaranteed to appear.

The origins trace back to Frank Ramsey’s 1928 paper on the foundations of logic, where a combinatorial lemma appeared almost as a side remark. That lemma grew into a field of its own: Ramsey theory, the systematic study of the patterns that must appear within sufficiently large or complex objects. Its charm lies in the fact that one can encounter deep theorems through problems that sound almost recreational.

An Introductory Example

To demonstrate, a classic example is the party problem. Suppose you invite several guests to a gathering. No matter how the acquaintance relations among them are arranged, can one guarantee that a group of them will either all know each other or all be mutual strangers?

To formalize this, represent each guest by a vertex of a graph. Place an edge between two vertices if those guests know each other, and leave it absent otherwise. The question becomes: for a given integer $n$, how many vertices are required to ensure the existence of either a clique $K_n$ (a complete subgraph on $n$ vertices) or an independent set of size $n$?

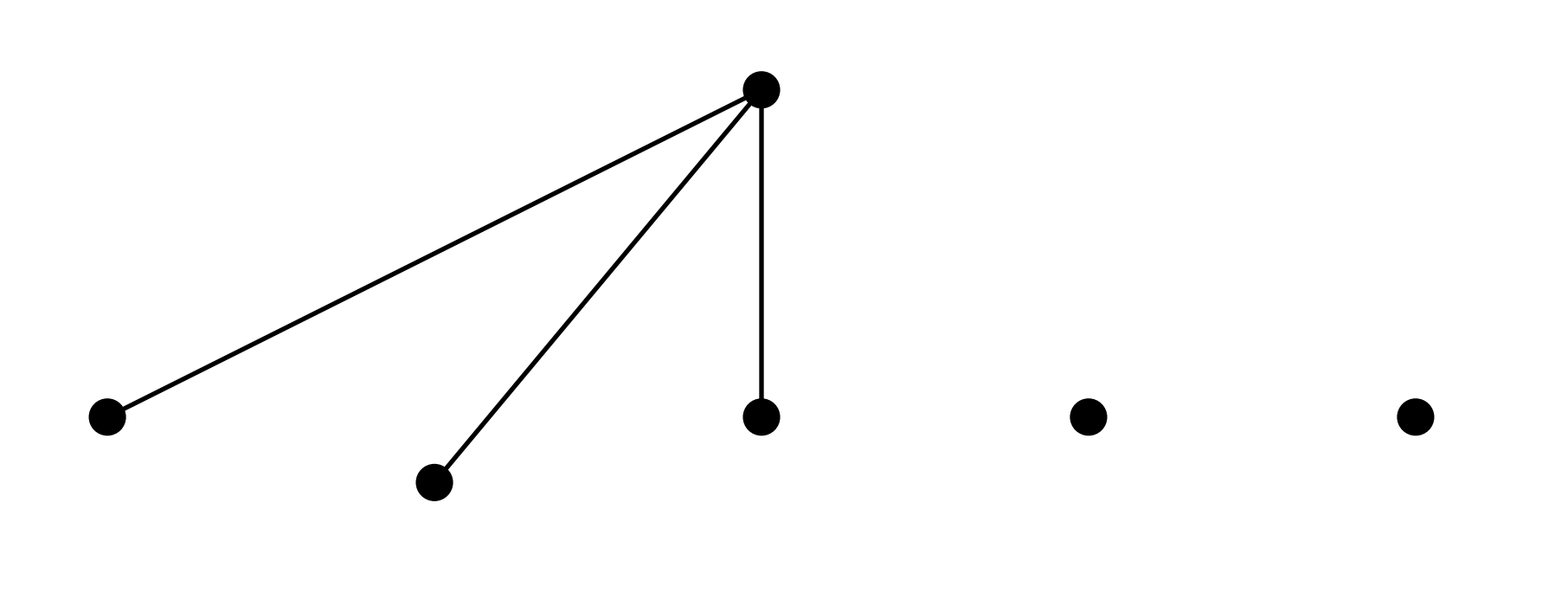

Consider the case $n=3$. With five vertices, it is possible to avoid both configurations: for example, a 5-cycle contains no triangle (3-clique) and no independent set of size three.

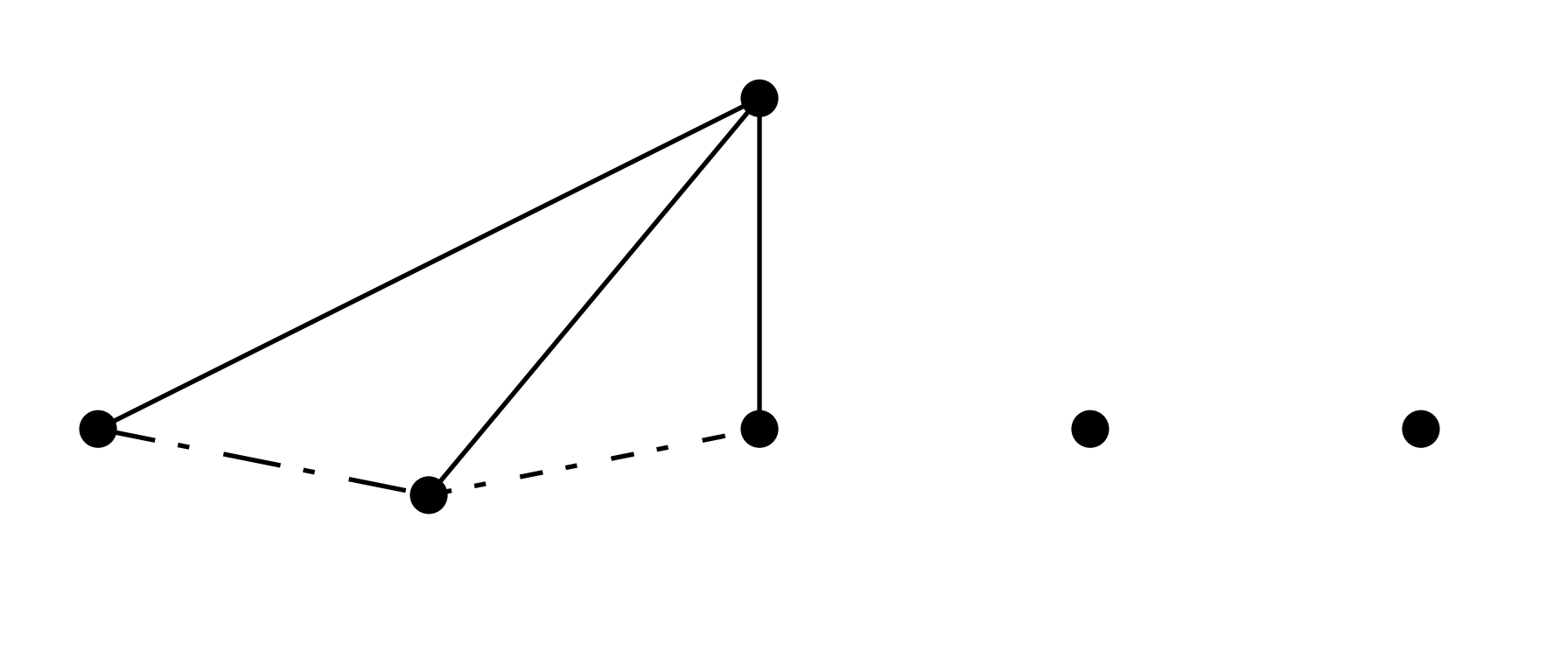

But with six vertices, such avoidance is impossible. Indeed, select any vertex $v$. Among the remaining five vertices, by the pigeonhole principle $v$ is either adjacent to at least three of them, or non-adjacent to at least three. Suppose the first case holds.

If any two of these neighbors are adjacent, they together with $v$ form a 3-clique. If none are adjacent, they themselves form a 3-independent set.

The second case is entirely analogous. Thus, in every graph on six vertices, either a 3-clique or a 3-independent set must occur, meaning that the minimum number of guests required to guarantee three mutual acquaintances or three mutual strangers is six. We write this as

\[R(3,3) = 6,\]the first nontrivial Ramsey number.

Elementary Ramsey Bounds

This example is the first instance of a much broader phenomenon, captured by the notion of Ramsey numbers. The Ramsey number $R(k,\ell)$ is defined to be the smallest integer $n$ such that every graph on $n$ vertices contains either a clique of size $k$ or an independent set of size $\ell$.

Equivalently, one may phrase the problem in terms of edge-colorings: consider a complete graph on $n$ vertices in which each edge is colored either red or blue. Then $R(k,\ell)$ is the least $n$ for which such a coloring must contain either a red $K_k$ (a $k$-clique all of whose edges are red) or a blue $K_\ell$ (an $\ell$-clique all of whose edges are blue), regardless of how the colors are assigned.

Theorem 1

We establish the general recurrence by induction. Observe first that the boundary cases are immediate:

\[R(2,\ell) = \ell, \qquad R(k,2) = k.\]Indeed, to avoid a red $K_2$, all edges must be blue, forcing a blue clique of size $\ell$; the argument is symmetric in the other case.

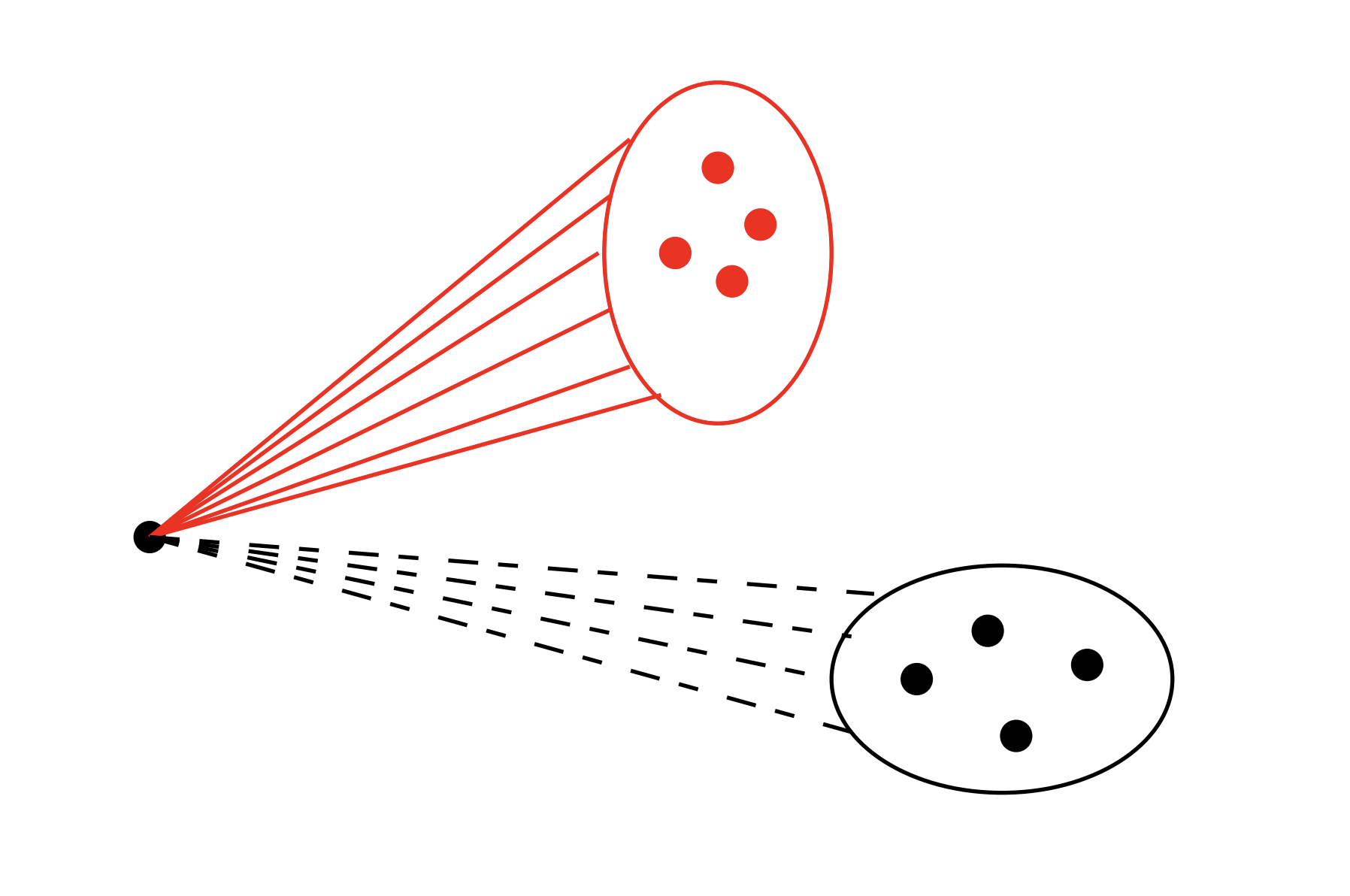

For the inductive step, suppose $k,\ell > 2$. Inspired by the proof of $R(3,3)=6$, consider a complete graph $G$ on $R(k-1,\ell) + R(k,\ell-1)$ vertices with edges colored red or blue. Fix any vertex $v \in G$. Among the remaining vertices, $v$ must be joined by at least $R(k-1,\ell)$ red edges or at least $R(k,\ell-1)$ blue edges.

-

If $v$ has at least $R(k-1,\ell)$ red neighbors, then within this red neighborhood we either find a red $K_{k-1}$ or a blue $K_\ell$ (by definition of Ramsey numbers). In the first case, adjoining $v$ produces a red $K_k$; in the second, we already have the required blue $K_\ell$.

-

Symmetrically, if $v$ has at least $R(k,\ell-1)$ blue neighbors, then either a blue $K_{\ell-1}$ arises (which, together with $v$, forms a blue $K_\ell$), or a red $K_k$ already appears.

In either case, the desired configuration is unavoidable. This establishes the fundamental recurrence

\[R(k,\ell) \leq R(k-1,\ell) + R(k,\ell-1),\]valid for all $k,\ell \geq 2$. $\square$

More specifically, we get the following bound:

Exercise 1

Meaning that the diagonal Ramsey numbers, $R(k, k)$, are bounded by the central binomial coefficient, $\binom{2k - 2}{k - 1}$, or simply, exponential.

Recent Breakthrough

One might wonder whether the lower bound for the diagonal Ramsey numbers grows exponentially as well. After all, the recent breakthroughs on the upper bound are only meaningful if the numbers themselves are truly exponential in scale. If there were even a slight chance that $R(k,k)$ could be merely polynomial (say quadratic or cubic), then every advance on the upper bound—whether $4^k$, $3.999^k$, or lower—would be largely beside the point.

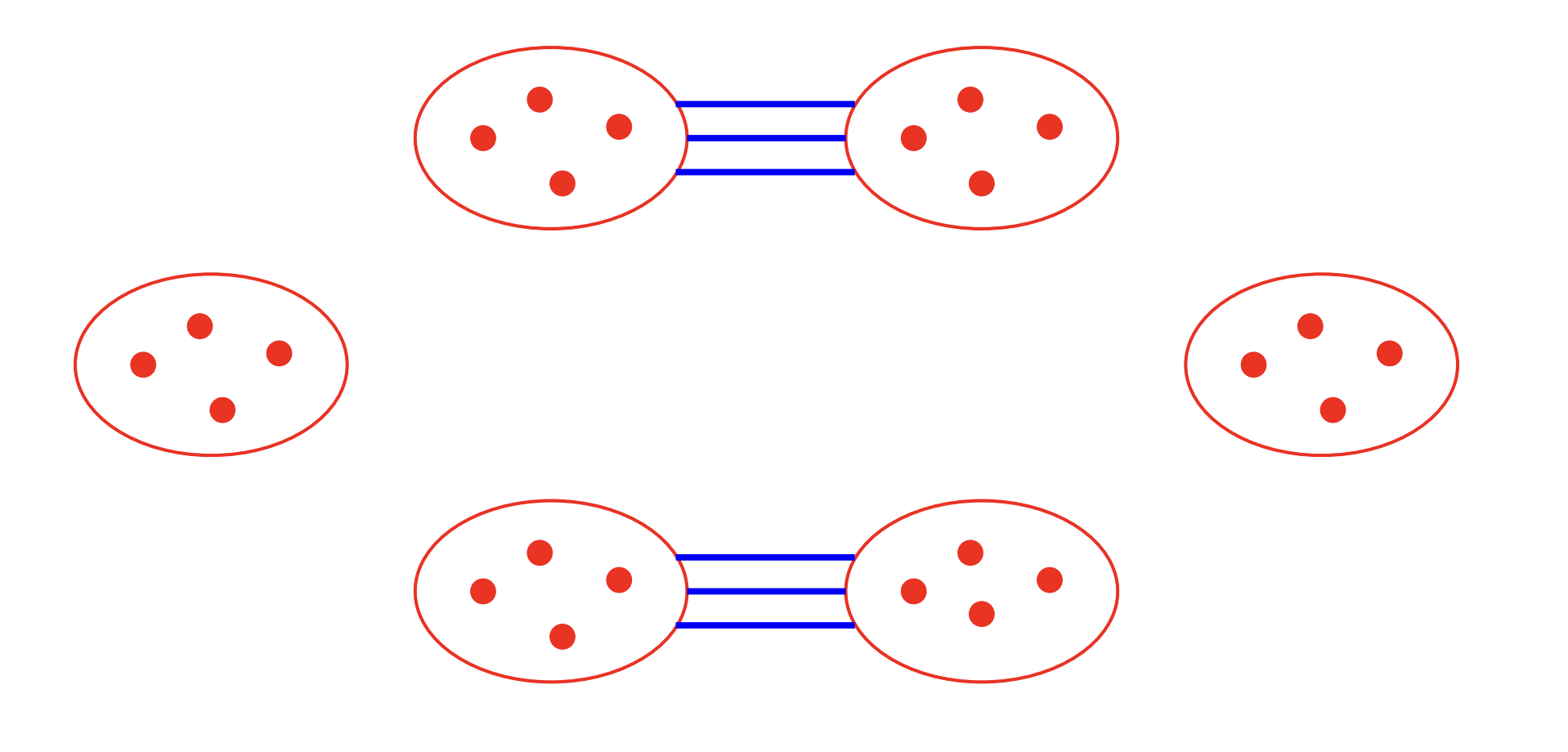

A natural approach to finding a lower bound is to construct colorings of large complete graphs in which no monochromatic $K_k$ appears. A natural idea is to partition the vertices into “blocks” and force every $k$-set of vertices to see both red and blue edges.

The simplest example is unremarkable: a single red clique on $k-1$ vertices avoids a red $K_k$, but only shows that $R(k,k) > k-1$, which we already knew. A modest improvement comes from two cliques of size $k-1$, colored red internally and blue across: any $k$ vertices include two from the same clique (a red edge) and at least one from the other (a blue edge), hence $R(k,k) \geq 2(k-1)$.

The idea extends naturally. Partition into $k-1$ cliques of size $k-1$, red inside, blue between. By the pigeonhole principle, any $k$-set contains two vertices from the same clique (a red edge) and two vertices from different cliques (a blue edge), so no monochromatic $K_k$ exists. This yields $R(k,k) \;\geq\; (k-1)^2.$

For decades, this quadratic construction marked the frontier of our knowledge. But quadratic growth, however elegant the argument, falls far short of exponential. To push beyond this impasse required a new philosophy, one that would loosen the demand for explicit construction.

A decisive advance came in 1947 with Erdős’s introduction of the probabilistic method. Rather than constructing a particular coloring, one analyzes a uniformly random red–blue coloring of $K_n$. If the expected number of monochromatic copies of $K_k$ is strictly less than one, it follows (by the first moment method) that there must exist a coloring with none. In this way, one can establish existence without explicit construction.

Formally, for a fixed $k$-set of vertices, the probability it forms a monochromatic clique is

\[2^{1-\binom{k}{2}}.\]Thus the expected number of monochromatic $K_k$ in a random coloring of $K_n$ is

\[\mathbb{E}X = \binom{n}{k}\,2^{\,1-\binom{k}{2}}.\]If $\mathbb{E}X < 1$, then some coloring contains no monochromatic $K_k$.

Using the inequality $\binom{n}{k} \leq (en/k)^k$, we obtain

\[\mathbb{E}X \;\leq\; \Big(\tfrac{en}{k}\Big)^k\,2^{\,1-\binom{k}{2}}.\]which is less than one for estimates

\[n \;\geq\; \Big\lfloor \frac{k}{e}\,2^{(k-1)/2} \Big\rfloor\]Hence

\[R(k,k) \;>\; \frac{1}{e\sqrt{2}}\,k\,2^{k/2}.\]and we have

\[R(k,k) = \Omega\!\;\big(k\,2^{k/2}\big). \square\]One can also consider edge-colorings with more than two colors. In this setting, the same question arises: must a monochromatic clique of some size still appear?

Theorem 2

We proceed by induction on the number of colors. The base case of two colors has already been established.

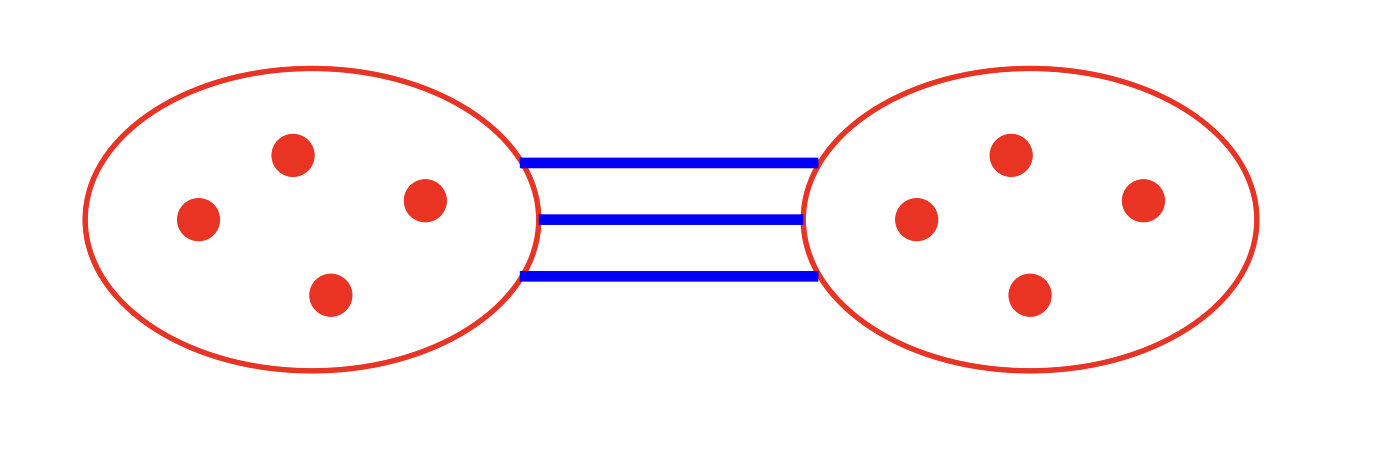

Suppose now that the statement holds for $n-1$ colors, and consider an edge-coloring with $n > 2$ colors. Merge the first two colors into a single “combined” color, so that we are effectively working with $n-1$ colors. By the inductive hypothesis, we know that $R(R(k_1,k_2), k_3, \dots, k_n)$ is finite.

Assume, for contradiction, that no monochromatic clique of size $k_i$ appears in color $i$ for any $i \geq 3$. Then there must exist a clique of size $R(k_1,k_2)$ whose edges are all in the combined color $(1,2)$. When we now distinguish between colors $1$ and $2$, this clique necessarily contains either a monochromatic $K_{k_1}$ in color $1$ or a monochromatic $K_{k_2}$ in color $2$. $\square$

Thus,

\[R(k_1,k_2,\dots,k_n) \leq R(R(k_1,k_2), k_3, \dots, k_n),\]which proves finiteness in the $n$-color case. $\square$

Ramsey Numbers for Hypergraphs

The notion of Ramsey numbers extends naturally from graphs to hypergraphs, where edges are arbitrary subsets of vertices rather than just pairs. For integers $i \geq 2$, the hypergraph Ramsey number $R^{(i)}(k,\ell)$ is defined to be the smallest $N$ such that, whenever all $i$-element subsets of ${1,2,\dots,N}$ are colored red or blue, one of the following occurs:

- there is a set $S_1$ of size $k$ such that every $i$-subset of $S_1$ is red, or

- there is a set $S_2$ of size $\ell$ such that every $i$-subset of $S_2$ is blue.

Equivalently, we are coloring the $i$-edges of the complete $i$-uniform hypergraph, and $R^{(i)}(k,\ell)$ is the minimum number of vertices needed to guarantee a red clique of size $k$ or a blue clique of size $\ell$.

Theorem 3

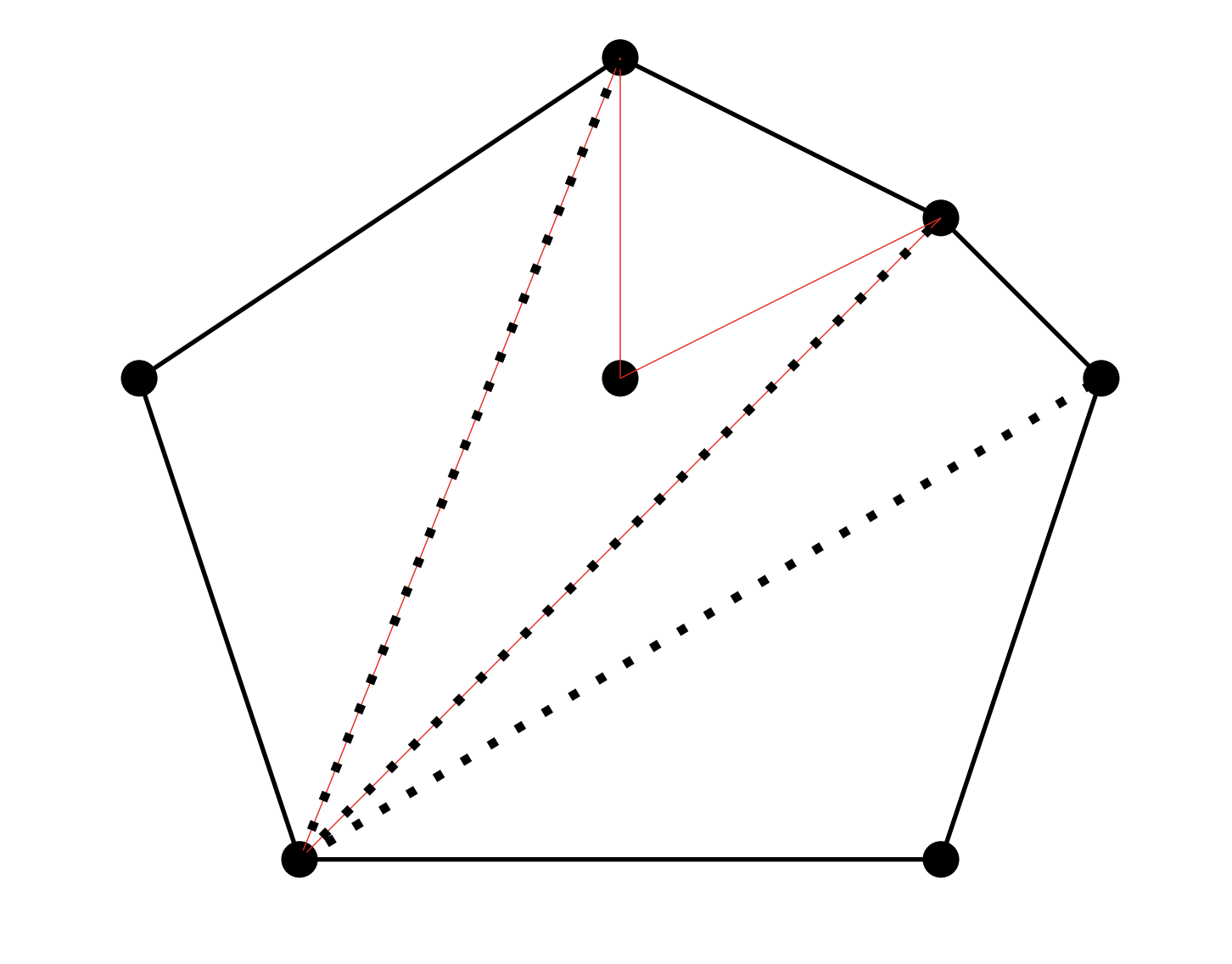

The guiding idea is to reduce the 3–uniform problem to a 2–uniform one by focusing on a single vertex and looking at how it interacts with the others.

Let us denote

\[a := R^{(3)}(s-1,t), \qquad b := R^{(3)}(s,t-1).\]Take a set $X$ of size $R(a,b) + 1$, and suppose every triple of vertices in $X$ has been colored red or blue. Our goal is to find either a red $s$-set or a blue $t$-set inside $X$.

Choose a vertex $x \in X$, and consider the remaining vertices $Y = X \setminus {x}$. Now, define a new coloring $c’$ on the pairs of $Y$: for each edge ${y,z}$, color it red in $c’$ if the triple ${x,y,z}$ was red in the original coloring, and blue otherwise.

In this way, the triples involving $x$ are encoded as edges in a 2–coloring of $K_Y$. Since $\vert Y\vert = R(a,b)$, Ramsey’s theorem for graphs applies: there is either

- a red clique of size $a$ in $c’$, or

- a blue clique of size $b$ in $c’$.

Case 1: A red clique of size $a$ in $c’$.

Let $Z \subset Y$ be this red clique. By definition of $c’$, every pair in $Z$ forms a red triple with $x$. Now restrict attention to the coloring of triples inside $Z$. Since $\vert Z\vert = a = R^{(3)}(s-1,t)$, one of two things must happen:

- $Z$ contains a blue $t$-set, which is already a blue $t$-set in $X$, or

- $Z$ contains a red $(s-1)$-set. Adding $x$ to this set produces a red $s$-set in $X$, because all triples involving $x$ and two vertices of the $(s-1)$-set are red.

Case 2: A blue clique of size $b$ in $c’$.

Similarly, let $T \subset Y$ be this blue clique. By definition of $c’$, every pair in $T$ forms a blue triple with $x$. Now consider the restriction to triples inside $T$. Since $\vert T\vert = b = R^{(3)}(s,t-1)$, we find either:

- a red $s$-set inside $T$, and we are done; or

- a blue $(t-1)$-set $U \subset T$. In the latter case, adjoining $x$ gives a blue $t$-set in $X$, since all triples in $U$ are blue, and all triples involving $x$ and two vertices of $U$ are also blue.

In both cases, we obtain the desired red $s$-set or blue $t$-set in $X$. This completes the proof. $\square$

Exercise 2 (General Recursive Bound)

Points in Convex Position

Although Ramsey’s theorem laid the formal groundwork, the broader spirit of what is now called Ramsey theory was rediscovered and popularized a few years later by Erdős. A particularly simple but striking application arose from a geometric problem posed by a young mathematician, Esther Klein, in 1933. Her question concerned the unavoidable appearance of convex configurations among a small set of points.

Theorem 4 (Klein, 1933).

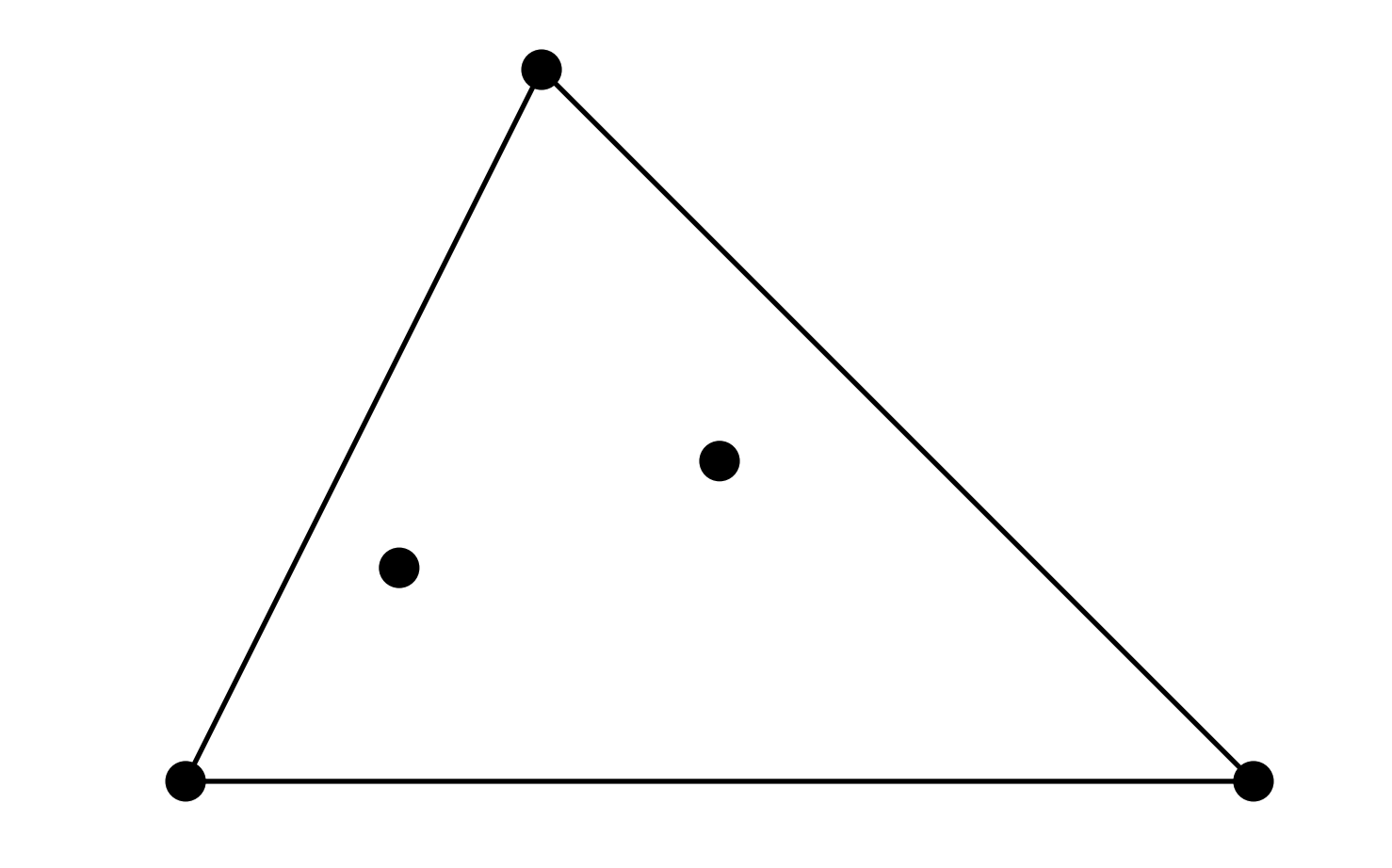

The argument is elegantly short. Consider the convex hull of the 5 points.

- If the hull already contains 4 or more vertices, those vertices form a convex quadrilateral and we are done.

- Otherwise, the convex hull is a triangle with exactly two interior points, as in the figure:

Draw the line through the two interior points. Since no three points are collinear, at least two of the three hull vertices must lie on the same side of this line. These two vertices, together with the two interior points, necessarily form a convex quadrilateral:

Thus in any configuration of 5 points in general position, a convex quadrilateral is unavoidable. $\square$

The problem raised by Klein can be extended in a natural way. Erdős asked: for a given integer $k$, is there always some finite number $N$ such that any configuration of $N$ points in the plane, with no three collinear, must contain $k$ points in convex position? This question, settled in joint work with Szekeres, is now regarded as one of the foundational results in combinatorial geometry.

Theorem 5 (Erdős–Szekeres, 1935).

The statement has the same character as Ramsey’s theorem: sufficiently large sets necessarily contain highly structured subconfigurations. To make this precise, let us encode the problem in terms of 4–uniform hypergraphs.

Given a set of points in general position, color each 4–subset red if it forms a convex quadrilateral, and blue otherwise. Define

\[N := R^{(4)}(k,5).\]By the definition of the hypergraph Ramsey number, there must exist either

- a set of $k$ points whose every 4–subset is red, or

- a set of 5 points whose every 4–subset is blue.

The second outcome is impossible, because Klein’s theorem shows that among any 5 points in general position, there are always 4 in convex position. Hence we are left with the first outcome: a set of $k$ points in which every 4–subset is red.

Suppose, for contradiction, that these $k$ points are not in convex position. Then the convex hull of these points is not a $k$-gon, and so some point must lie strictly inside a triangle formed by three others. These four points fail to form a convex quadrilateral, contradicting the assumption that every 4–subset was red.

Thus all $k$ points lie in convex position, completing the proof. $\square$

Fermat's Last Theorem Over Finite Fields

At the turn of the twentieth century, Fermat’s Last Theorem was still a central mystery. A natural idea was to examine the problem modulo a prime $p$. After all, if there were an integer solution to

\[x^n + y^n = z^n,\]then reducing everything modulo $p$ would also give a solution to

\[x^n + y^n \equiv z^n \pmod{p}.\]Perhaps, then, one could hope to prove Fermat’s Last Theorem by ruling out all such congruences.

But this approach fails. Dickson (1909) showed that for large primes $p$, the congruence has infinitely many solutions. Though his argument was very algebraic heavy, a few years later, Issai Schur rederived this impossibility with a surprisingly elementary combinatorial argument. His result, now called Schur’s theorem, is widely considered the beginning of additive combinatorics.

Theorem 6 (Schur, 1916).

The proof is a direct application of Ramsey’s theorem. Let $N = R(3,3,\dots,3)$ be the Ramsey number for $r$ colors, where each parameter equals 3. That is, $N$ is the smallest integer such that any edge-coloring of the complete graph on $N$ vertices with $r$ colors must contain a monochromatic triangle.

Now suppose we color the integers ${1,2,\dots,N}$ with $r$ colors by some function $\phi$. Construct a complete graph on vertices labeled $1,2,\dots,N$. For each edge $(i,j)$ with $i< j$, assign it the color $\phi(j-i)$. In other words, the edge color records the color of the difference between its two endpoints.

By the definition of $N$, this graph must contain a monochromatic triangle. Suppose its vertices are $i< j < k$. Then the three edges of the triangle have colors $\phi(j-i)$, $\phi(k-j)$, and $\phi(k-i)$. Because the triangle is monochromatic, all three of these differences have the same color. But notice that

\[(k-i) = (k-j) + (j-i).\]Thus we have three numbers of the same color, $x = j-i$, $y = k-j$, and $z = k-i$, which satisfy $x+y=z$.

This shows that in any $r$-coloring of ${1,\dots,N}$, there must be a monochromatic solution to $x+y=z$. $\square$

Schur’s theorem shows that additive relations like $x+y=z$ cannot be avoided once the integers are colored in finitely many ways. This idea extends naturally to Fermat’s equation in finite fields.

Theorem 7 (Dickson, 1909).

Consider the set of all $n$th powers in $(\mathbb{Z}/p\mathbb{Z})^\times$:

\[H = \{x^n : x \in (\mathbb{Z}/p\mathbb{Z})^\times\}.\]This is a subgroup of $(\mathbb{Z}/p\mathbb{Z})^\times$ of index at most $n$. Partition the nonzero residues into cosets of $H$. Assign a distinct color to each coset, so we obtain a coloring with at most $n$ colors.

Now, by Schur’s theorem, if $p$ is large enough (specifically, if $p-1 \geq N$, where $N$ is the number guaranteed by Schur’s theorem for $n$ colors), there exist three numbers $x’,y’,z’$ of the same color such that

\[x' + y' = z'.\]Being the same color means that $x’,y’,z’$ lie in the same coset of $H$. Suppose this coset is $\alpha H$. Then we may write

\[x' = \alpha x^n, \quad y' = \alpha y^n, \quad z' = \alpha z^n\]for some $x,y,z \in \mathbb{Z}/p\mathbb{Z}$. Substituting into the relation $x’+y’=z’$ gives

\[\alpha x^n + \alpha y^n = \alpha z^n.\]Since $\alpha$ is invertible, dividing through yields

\[x^n + y^n \equiv z^n \pmod{p}.\]Thus Fermat’s congruence has a non-trivial solution. $\square$